4. Notes and Scales

What is a note?

A note represents a sound. More precisely, it represents a frequency. To understand this better, we first need to comprehend what sound really is.

What is Sound Really?

When we listen, we perceive the vibration of the air. To visualize this phenomenon, in the graph below, the small blue dots represent the air particles.

When we play a sound, the speaker's diaphragm vibrates. This vibration, in turn, moves the air particles. As a result, the movement creates areas where there are more particles and areas where there are fewer.

We can represent this phenomenon with a wave. You can see it in the graph below the air particles.

In this representation, the peaks of the wave indicate areas where the air is more compressed. Conversely, the troughs indicate areas where the air is more relaxed.

Similarly, we can also represent the movement of the speaker with a wave. In this case, the peaks show when the speaker pushes outward, while the valleys show when it contracts.

Now, what happens when these vibrations reach us? These air vibrations reach your ear and make the eardrum vibrate. Then, this vibration travels through the ear and moves some microscopic "hairs" in the auditory cells. Next, these cells send electrical signals to the brain. Finally, the brain converts these electrical pulses into what we perceive as sound.

Now that we understand the mechanism of sound, you can interact with the graph by pressing the piano keys. Each note represents a specific frequency. For example, the note C2 (Do) has a frequency of approximately 65 Hz.

Hertz (Hz): Unit that measures vibrations per second. 65 Hz means that the wave goes up and down 65 times per second. In other words, your speaker's diaphragm vibrates 65 times per second.

Therefore, the note C2 is the sound you hear when your speaker vibrates 65 times per second.

Higher notes have higher frequencies. This means they vibrate faster and, consequently, your speaker also vibrates faster. To check this, play C2 and C3 on the piano and compare them. You will see that C3 vibrates twice as fast as C2.

Now comes the interesting part: When one wave vibrates twice as fast as another, our brain hears them as the same note. It's just that one sounds higher than the other. This is the reason why C2 and C3 share the same name (C). The number simply indicates which one is higher.

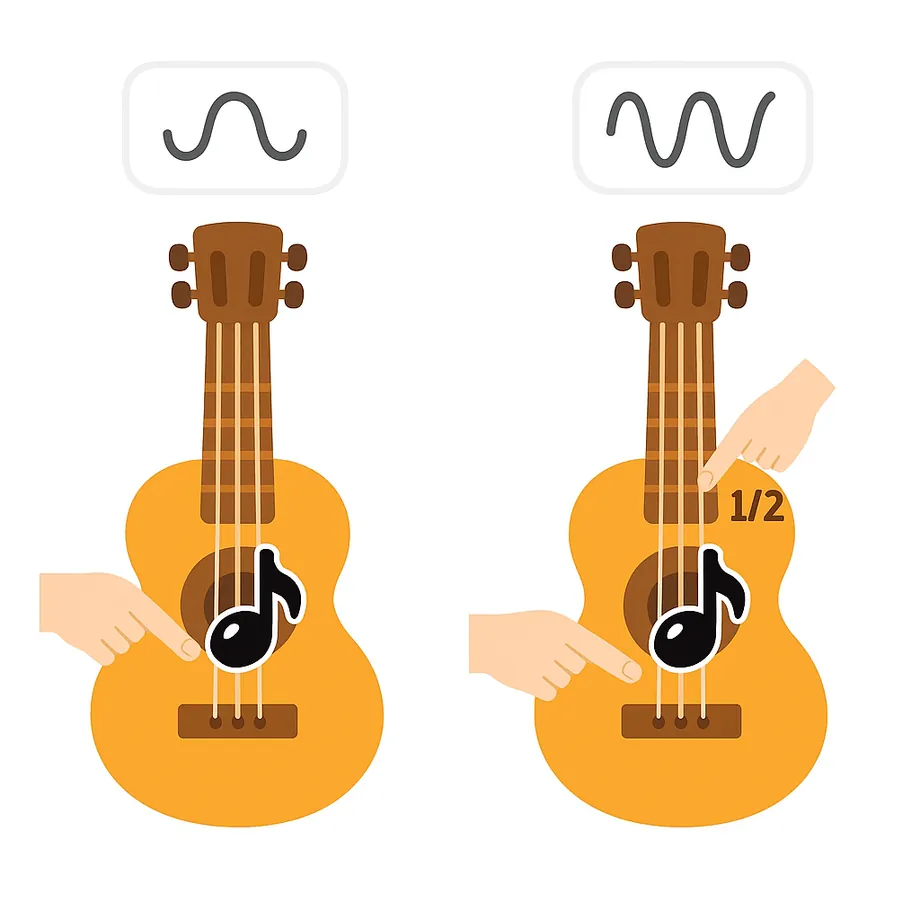

To visualize this concept, look at the following image. C3 has double the frequency of C2, and yet our brain perceives them as the same note:

Does this have any practical use? Of course it does. In fact, this is exactly how a guitar works. If you pluck a string, it sounds a note. Now, if you press the string with a finger to shorten its length by half and pluck it again, the note will be the same but higher in pitch. There is a metal bar on the guitar that marks this exact point.

The 12 Notes

We already know that by doubling any frequency, for example 261Hz (C4), we get 524Hz (C5), the same sound but higher. So now we have our first 2 notes!

But what about the other notes? This is where the fundamental decision of Western music comes into play: we divide the frequencies between C4 and C5 into 12 equal parts. In this way, we obtain 12 new notes. In other words, we divide the range between 261 Hz and 524 Hz into 12 parts.

To visualize it better, we will represent C4 and C5 as 2 white circles. The same note, but one higher than the other.

As a result of dividing this range into 12 equal parts, we obtain 12 new notes. Below, I show you their 2 ways of naming them. You don't need to memorize their names for now.

Anglo-Saxon notation: C, C♯, D, D♯, E, F, F♯, G, G♯, A, A♯, B, C

Latin notation: Do, Do♯, Re, Re♯, Mi, Fa, Fa♯, Sol, Sol♯, La, La♯, Si, Do

These are the 12 notes of a piano (if you count the white and black keys).

These 12 notes are present in all instruments: piano, violin, flute, guitar, trumpet... They all use only these 12 notes.

If we added more circles to the left or right, they would be the same notes but higher or lower. To obtain more different notes, we would have had to make more than 12 divisions. However, in the history of Western music, it was decided that 12 was a good number. As a consequence, all the songs you hear (classical music, rock, electronic...) use only these 12 notes.

Scales

Now that we know the 12 available notes, an interesting question arises: Do we use all of them in a song? The answer is no. But why not use them all 🎹🤩🎹?

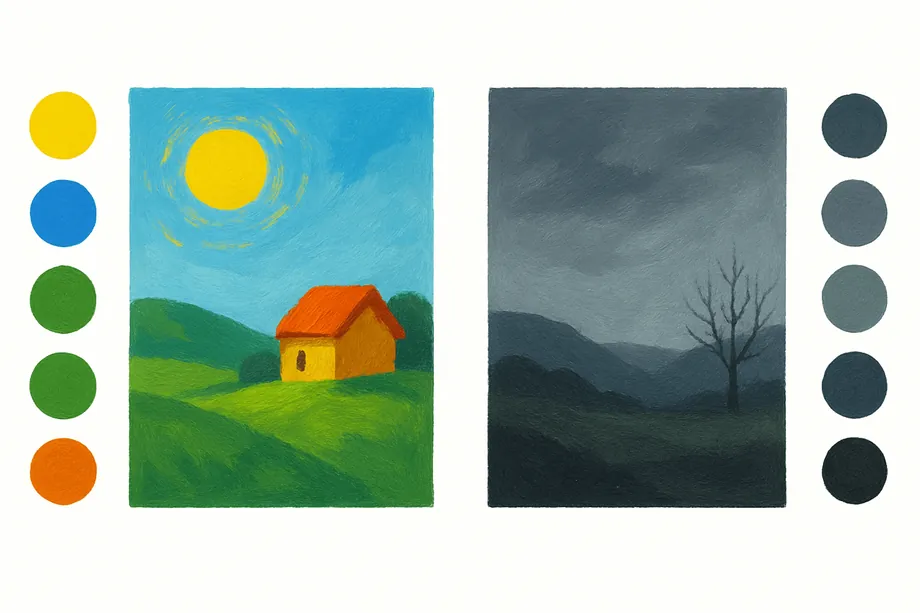

To understand this, let's think of an analogy with painting: when you paint a picture, you don't use all the colors available. If you want a cheerful painting, you use bright colors. On the other hand, if you want a sad painting, you use dark colors. If you want to convey tranquility, you use soft colors. Rarely will you use all the colors in the same painting. Ultimately, you choose a color palette based on the feeling you want to convey.

The same happens with music: from these 12 notes we only choose some according to what we want to convey. Instead of "color palette," in music we talk about Scales.

Scales

For example, these are the most used notes in the music you listen to. It's called Major Scale. It's simply a palette of notes, a choice of notes.

You might be wondering: What notes are they 🧐?, C, A, G...? I only see white circles 🤪? That's the point: the names of the notes don't matter. What matters are the spaces between them. In fact, the spaces are what give style to our scale.

Let's see how it works. In this case, the pattern is 2-2-1-2-2-2-1. We start on C4 (the first circle). We take 2 steps and select the third note. Next, we take another 2 steps and select the fifth note. Then, we take 1 step and select the sixth circle... and so on...

In music theory, these jumps have a name. When we jump 2 notes, it's called a whole step, and when we jump just 1 note, the minimum jump, it's called a semitone.

Now comes a fundamental point: it doesn't matter which note you start on. As long as you make the same jumps, the scale will be the same. It's like going up and down a staircase: if you go up 2 steps, down 1, and then up 3, it doesn't matter if you start on step 10 or step 34. The movement is the same.

Here we have the same Major Scale but starting on different notes. If you notice, the jumps are the same. The selected notes have changed, which is why we say they don't matter; we are still in the Major Scale because we made the same jumps. And the style of the scale is the same.

Why choose those jumps and not others? This palette/scale is frequently used for cheerful or lively songs.

But there are many more scales! Let's take a look at some to compare... 🎨

Minor Scale - 2-1-2-2-1-2-2

Unlike the Major scale, this scale sounds darker and less vibrant. Generally, the Major scale is used for cheerful songs, while the Minor scale is used for sadder songs. Although this is not always the case. The Major and Minor scales are the two most commonly used in current music.

Blues scale - 3-2-1-1-3-2

Notice how, just by selecting a different note spacing, we achieve a characteristic blues music style.

Double Harmonic Scale - 1-3-1-2-1-3-1

This scale, for its part, has a distinctive Arabic style.

In Sen Scale - 1-4-2-3-2

This, on the other hand, has a traditional Japanese style.

How do these scales sound?

To hear these scales in action, if you press the blue Play button, you will hear a well-known song in each of the scales. The song only uses the notes from each scale (only uses the black circles).

Major Scale:

Minor Scale

Listen to these 2 very similar tracks, one played in Major Scale and the other in Minor Scale. See if you notice the difference.

Blues scale

Double Harmonic Scale

It has an Arabic style.

In Sen Scale

It has a Japanese style.

If you're up for it, you can try creating your own scale!

It is important to note that the song uses the same positions within the scale in all examples (it plays... third white circle, fourth white circle, fifth, fifth, fourth, third...). But the song will NOT sound the same, because the white circles do not have the same distance between them in different scales. In other words, even though we ascend and descend in the same way in the scale, the height from the third step to the fourth is not the same in all scales.

For example, look at the following 2 scales. If I play the first circle and then the second (if I play the first and second notes of the scale). In the first scale, I made 2 jumps, but in the second scale, I made 3.

Now, what happens if we use the same scale, the Major Scale, but starting from a different note? The distance pattern here will indeed be the same in both: 2-2-1-2-2-2-1. In this case, it will be like going up and down the same steps, and those steps will have the same height, only we start from a different rung. Therefore, the song will sound the same, just a bit lower or higher.

Building a Piano

We have said that the Major Scale is the most used. Therefore, the white circles are the notes we will use the most, while the black ones are the notes we will use less. If you had to build a piano, where would you place the black notes?

Probably you would place them further apart and smaller. Does this arrangement sound familiar? Exactly, it's the same as any piano!

Therefore, when you wonder why there are black keys in the middle of some white keys and not in others, the answer is simple: it's due to the number of jumps we made when selecting the note palette. In some jumps, we skipped notes (black circles or black piano keys) and in others, we did not (two white circles together or 2 white keys together). If we had considered that the Minor Scale was going to be the most used, the black and white keys of the piano would be different.

In the next lesson, we return to Strudel to put all of this into practice 👉>>